In late 1949, the next the product was already being developed In a rushed program that was a complete contrast to the years Porsche had spent developing the Beetle prototypes. Eventually named Type 2 Transporter by the factory, the new vehicle later acquired, many other names reflecting its roles and the countries that embraced it – Bus, Bulli, Samba, and Camper were just the start.

Before and during the war, Porsche and explored the cargo-carrying potential of the Beetle, cutting away the rear bodywork of sedans to accommodate a pickup-type body, then developing van-life rear bodywork for the 1940 Type 81. In September 1945, Rudolf Brörmann had numbered a delivery vans built were used within the factory.

But there was clearly a market. Postwar Europe was starved not just for cars but for commercial vehicles too; as consumer spending power gradually grew, so did the need for vehicles to deliver all those radiograms and washing machines. In 1948, 60 percent of VWs went to domestic customers, mostly businesses, which had preferential rates.

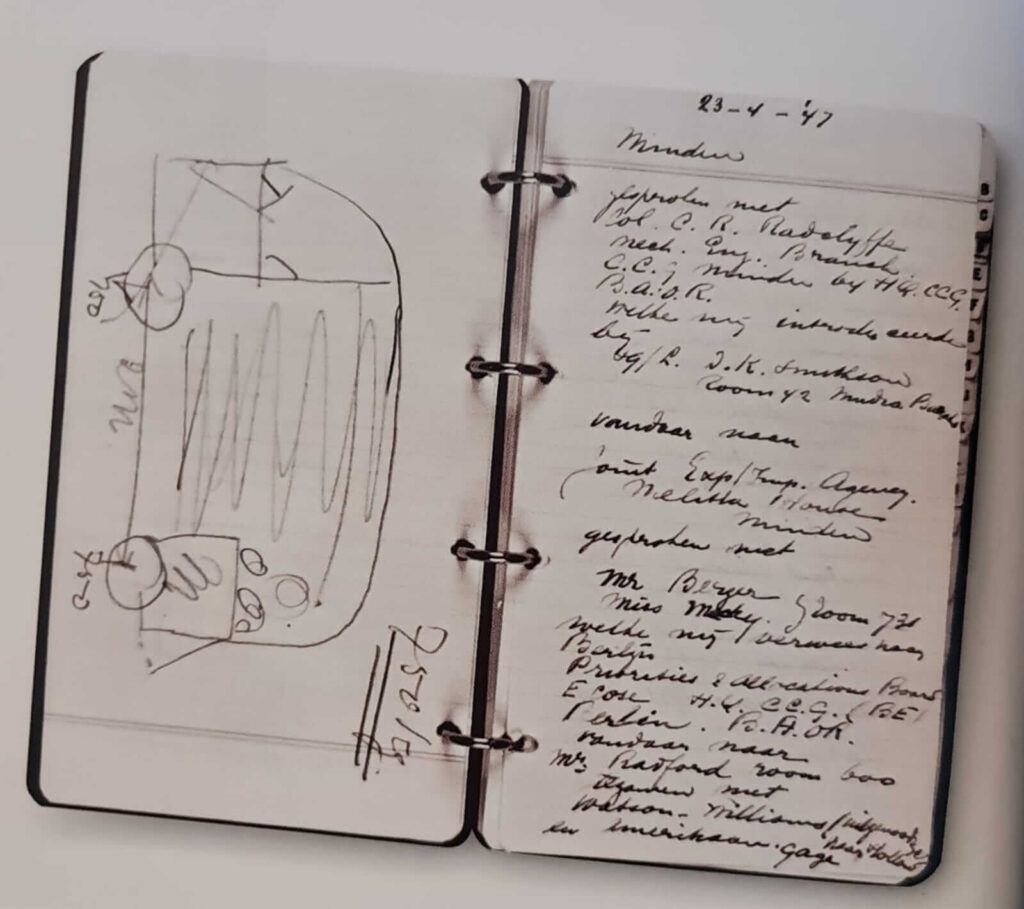

Whose idea was the Volkswagen Van? Although Nordhoff was said to be the principal instigator, it I now accepted that while negotiating the first export deal to buy Volkswagen sedan on April 27, 1947, Dutch importer Ben Pon sketched the box-shaped outline of a delivery vehicle that enclosed a Beetle engine at the rear and had the driver positioned over the front wheels. His inspiration is said to have been the Plattenwagens, rear-engined open vehicles built to carry parts around the factory. As recounted by Hirst, the Plattenwagens came into existence only after his own request for army forklift trucks was turned down. Hirst came up with the idea of taking a placed, with the driver sitting above the engine at the rear to avoid an extra steering link and allow tight turning radius.

According to Hirst, Pon initially wanted to sell just Plattenwagens to Dutch companies. But Dutch authorities refused because drivers were required to be seated at the front of their vehicles. Pon’s now-famous sketch was dashed off during a meeting with Hirst, who recommended Pon discuss it with Radclyffe, who in turn ruled out production of a new production of a new product at a time when the priority was making the standard Beetle saleable.

Built Only to transport parts over the vast Wolfsburg factory complex, the Beetle-engined Plattenwagens (This circa 1948) were the ancestors of the Transporter van. The last Plattenwagen was built as late as 1973.

Pon next turned to Heinz Nordhoff for backing and got it. Alfred Haesner was put to work on the creation of the new Volkswagen van while also charged with creating the Export Beetle. In November 1948, he presented Nordhoff a choice of two designs, both with a resemblance of the Ben Pon sketche. One had a flat front and the other a slightly curved and racked cab. Wooden scale models were made at the Institute for Flow Mechanics at the Techinical College of Braunschweig (now university), and a report in March 1949 favored the round-nose front.

The first Prototype VW29, was ready for testing on March 11, 1949. Contrary to Nordhoff’s later claims that the new classics vans designed from the outset, it was initially thought that the body could simply be a strengthened version of the Beetle design, with the upper half bolted to a platform chassis. Within a month, the weight of the central load had broken the frame. Haesner had to restart from scratch, but Nordhoff would not budge from his

With Nordhoff taking a close interest in the smallest details of the van project, Haesner and his team constructed a new prototype with an all-in-one body shell, otherwise known as unitary construction, still a rare design in cars and trucks of the day. However, it was not quite full unitary construction: It can be argued that there was a separate chassis of sorts. The floor and body were welded rather than bolted together on top of subframe, with five substantial crossmembers between the axels. The boxed-in engine compartment also gave good (twisting) strength.

Thus the load area, a self-supporting steel structure, carried the driver and passenger at the front and the engine and gearbox at the rear, a non-synchromesh “crash” type where the driver had to double declutch to achieve smooth gear changes. This was taken from the Beetle but with a much longer linkage to connect to the gear lever at the front of the vehicle. The lower gear ratios of the military Kübelwagen helped van drivers keep up. The final driver was through a spiral-bevel gear to Beetle-type swinging half axles and then through a secondary spur reduction gear in the hubs (again from the military Volkswagens), which gave better ground clearance than the Beetle.

The Transporter benefited from hydraulic brakes, launched on the Export Beetle in 1949. The all-independent suspension design of the Beetle was also adopted, the front axle and shock absorbers uprated to handle future power increases. Steering a worm-and-roller system as with the Beetle, was controlled by a wheel that sat virtually flat in the driver’s lap.

Once launched, there would be quibbles about power. As author and Volkswagen historian Richard Copping points out, contemporary German small vans were as low-powered as the first 24.5-brake horsepower Transporter, or even weedier, with two-cylinder two -stroke engines. The DKW Shnellaster van, pickup, and minibus, whose name translates misleadingly as “fast transporter”, boasted just 20 brakes horsepower. The short-lived Goliath GV (1951-1952) started with 16 brake horsepower and later upgraded to 21.

The first VW29 prototypes, having been rebuilt to the new chassis specification, were driven some 7,546 miles (12.000 Km) at Volkswagen’s proving ground, on public roads north of Wolfsburg, and along the West German border, as well as in Harz Mountains. They proved themselves well, and Nordholff ordered ne prototypes to test other future possibilities he had planned; it was to be offered as a pickup, eight-seat minibus, ambulance, police car, and postal service vehicle.

Many details, such as the need for stronger door hinges, a windscreen wiper, and relocation of the fuel filler inside the engine bay, took the development program right up to Nordhoff’s press launch date, postponed from November 6 to November 12. Even the development was not finished, and there would be many more changes in its early years.

When the new Volkswagen vans were demonstrated to the press, Nordhoof made no mention of Pon. He said that he had planned the vehicle just over a year prior during a car journey with Alfred Haesner. Hundreds of market-research interviews, Nordhooff said, concluded that the standard practice of putting bodywork capable of carrying a 1.102-pound (500 kg) load onto medium-size car chassis and thus placing most of the load over the rear axle. Nordhoff also stressed that the company would have placed the engine at the front had it been the best solution. He started that Volkswagen had begun by basing that design, the ore obvious route.

Volkswagen’s own treasured 1950 van. The curb weight of the first versions was target 1,874 pounds (850 Kg), and when it was exceeded, the rear bumper was simply left off. It returned in 1953.

The Beetle engine seems lost inside this early engine bay. The fuel tank is at left, spare wheel right. The huge VW logo took the place of a window until November 1950

This view from the inside of a 1954 Transporter shows its austere trimming, with card panel doors and no headlining. A split-front screen enabled two sheets of cheaper flat glass to be used.

There were three square meters of floor space plus one square meter over the engine, with the fuel tank, spare wheel, and battery housed in the engine compartment. The load area was exactly between the axles, Nordhoof explained; laden or unladen, the axles load was always equal, with a driver and one or two passengers in front and the engine at the other end. This load area was accessed via a pair of side doors the extended from the curb to the roof. At first there was no rear door to the load bay, so a 1949-1950 Transporter could be backed into the tightest space. The van weighed and could carry 1,870 pounds (850 Kg), a “best ever performance for a van of this size, with a weight to load ratio of 1:1.” Fully loaded, top speed was claimed to be more than 46 miles per hour (75Km/h), with a hill-climbing ability of 22 percent and a fuel consumption of 2 gallons per 62 miles (9L per 100Km). The drag factor was claimed to be CW 0.4.

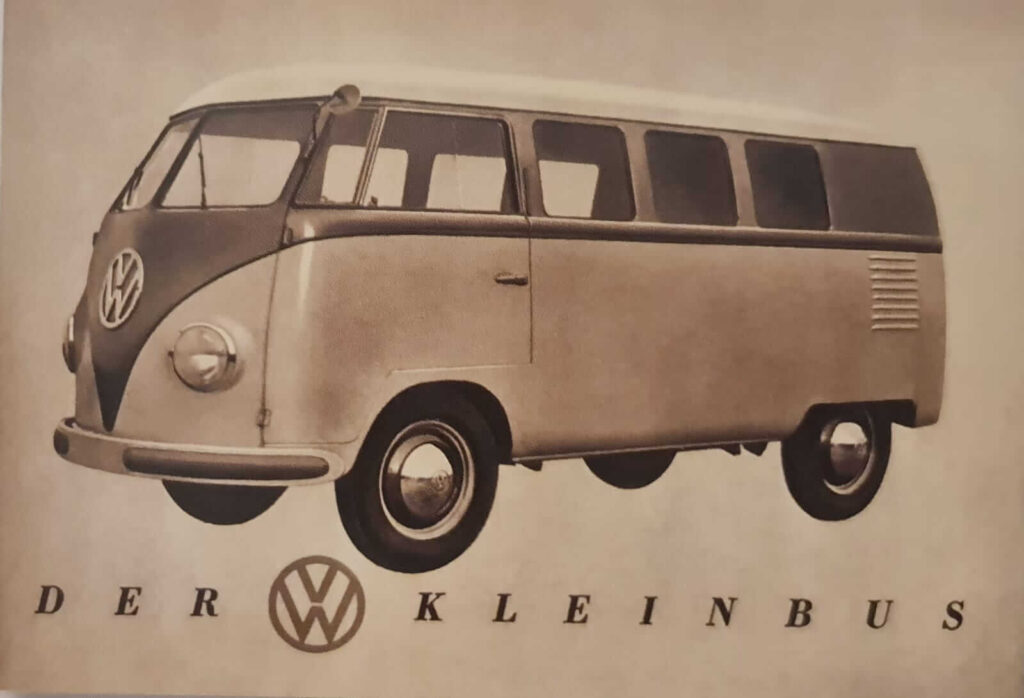

The Kleinbus, or “Little bus”, was the first passenger-carrying derivative of the 1950 Transporter and was promoted as a car capable of carrying eight people in comfort.

Unveiled at the Geneva Motor Show in March 1950 without much fanfare or attention, the Transporter made in tentative way into production alongside the Beetle at Wolfsburg, where workers produced 81,979 Beetles that year alone. The Transporter was initially built as a delivery van, with ten leaving the production line each day. In May, the Kombinationskraftenwagen, or Kombi, joined the range. Using the van structure but with side windows and easily removable bench seats, it was a prototype people carrier. The Kleinbus, or Microbus, came later the same month, designed to carry seven, eight, or nine passengers and fully trimmed to car standards. The year ended with total Transporter production of 8,058 units, of which 5,662 were vans, 1,254 Kombis, and 1,142 Microbuses. The Volkswagen Transporter in its various iterations was set to flourish alongside the Beetle in the new decade.

A 1950s Kombi snack bar at Wolfsburg, illustrating the useful ability to load from the sidewalk side. The difference in length to a Beetle was minimal.

Copyright: Motorbooks; Volkswagen beetles and Buses, Smaller and Smarter, by Russel Hayes. 2020 Quarto Publishing Group USA Inc.